Chronobiology is the study of the temporal organization of biological systems and processes in relation to physiology and behaviour. Or to put it simply, the science of the internal clock. But what is the internal clock?

The inner clock

All organisms across the biological phyla have an internal clock, from simple fungi to humans. It regulates the entire physiology, from gene expression to behavior, including our sleep/wake rhythm. It is characteristic that the internal clock has an endogenous periodicity of only about 24 hours. This is why it is also called the circadian clock (from the Greek circa = approximately, dies = day). Due to this approximate 24-hour periodicity, it must be regularly compared with the actual 24-hour outside day. Insufficient synchronization can have negative consequences for sleep and health. This daily correction of the internal clock is similar to the regular adjustment of old pocket watches, which are always a few minutes off.

Timer

The environmental signals that can set the internal clock are called zeitgebers. The most important zeitgeber for humans is sunlight and its rhythm, which is determined by the natural sunrise and sunset. But artificial light also plays a major role here. This was clearly demonstrated by the well-known Andechs bunker experiments of the 1960s under the direction of Prof. Jürgen Aschoff. We have known for over 10 years that it is specialized retinal ganglion cells that transmit day/light information via the optic nerves to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain. As the central coordination point, the SCN sends signals to all cells of the organism via nerve and blood vessels. This means that every cell knows what time it is and what function this cell now has to perform in order for the entire organism to function properly.

Owls, larks and more

However, each person’s internal clock ‘ticks’ individually, which is why each person is synchronized differently with their environment. This is why there are different chronotypes (Greek chronos = time) such as early ‘larks’ and late ‘owls’. Comparable to body size, the chronotypes in the population are normally distributed, with the extreme early and late types at either end. The internal clock of early chronotypes has a period shorter than 24 hours. You get tired earlier and wake up early in the morning, usually without an alarm clock. Late chronotypes get tired later and sleep further into the day because their internal clock has a period that is longer than 24 hours. The latter often need an alarm clock to get to work on time. In fact, over 70% of the working population use an alarm clock on working days, as Prof. Till Roenneberg at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) Munich found out. Prof. Roenneberg held the first professorship for chronobiology in Germany at LMU Munich from 2001 to 2018.

Lack of sleep

The data from Till Roenneberg’s Munich group shows that most people in our society do not wake up on their own to get to work on time. They therefore suffer from a chronic lack of sleep. We know the consequences of sleep deprivation for health from controlled laboratory studies. These can be serious and expensive in real life.

This particularly affects people who work shifts, which is an extreme but also widespread form of ‘living against the clock’. However, we also know today that daylight saving time alone can mess up your internal clock. A third example is the internal clock during adolescence, which is often much too late for school start times. Starting school later is very important because the current school system leads to chronic sleep deprivation, especially in adolescents, and has a significant negative impact on school performance. The need for action is therefore beyond question.

Sunlight and the internal clock

But what exactly characterizes a ‘life against the internal clock’? Here is a comparison: the internal clock works in a similar way to a swing. Depending on the point at which the swing is pushed, the swing continues to swing either faster, slower or unaffected. In the same way, the internal clock is influenced by light impulses, because light represents the external impulses. Depending on the phase position of the internal clock, i.e. when the SCN “sees” light, the internal clock is either set forward, set back or not influenced. Light at the wrong internal time, e.g. at night, can throw the whole organism out of sync. The mechanisms of the internal clock have been decoded in many intelligent experiments in recent years, for example by Prof. Achim Kramer and his team at the Charité in Berlin.

Conclusion

This clearly shows that chronobiology is a fundamental science with a clear reference to human life. Because almost everything that has to do with this touches on the topic of natural rhythms: Medical rehabilitation, work, shift work, education, health prophylaxis, healthy sleep and much more. One challenge for the future is to test and apply the findings of basic research in real life. This requires a pioneering spirit – as in the days of the Andechs bunker trials – and enthusiasm on the part of everyone involved.

The opportunities to open up scientifically to the complexity of the human being as an individual are still often confronted with economic cost/benefit calculations. However, this means that we very quickly stifle any real assessment of a possible profit. Even if a benefit can be identified, it is initially difficult to quantify its value. Nevertheless, the costs of ignoring this are enormous. The sleep deficit of its population costs the German economy almost €50 billion.

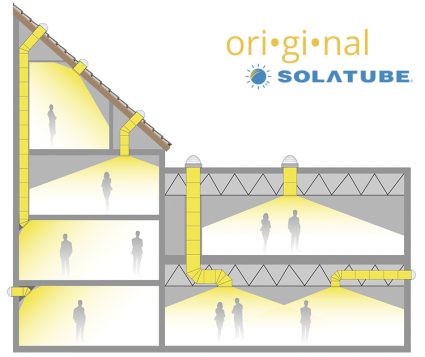

It is therefore not only chronobiologists who would like to see a broader public discussion of what can be achieved with current and future findings from this field, particularly with regard to human health. And the prospects are good. Close cooperation between science and industry is increasingly leading to the development of an industry based on the findings of chronobiology. One example is the“feel-good glass ” developed at the Fraunhofer Institute in Würzburg, or so-called solatubes, which direct sunlight into closed rooms.

2020 will be the decade of chronobiology, and it will enter people’s consciousness as part of occupational health management. I am sure of that.